Restored Zhongshan Building Provides a Community Space for KL’s Arts Scene

A restored building that previously housed the Selangor Zhongshan Association now aims to become a community hub for the KL arts scene. Will it thrive?

Side view of Zhongshan building. Image courtesy Eiffel Chong

The Zhongshan is the brainchild of the owners of OUR Art Projects gallery, Liza Ho and Snow Ng. Boasting a freshly-painted white facade, distinct colonial features from the fifties, and its name in elegant vertical traditional Chinese lettering down the side of the building, the Zhongshan is tucked away at the bottom of Jalan Rotan.

Ho and Ng share a unified theory and vision for the Zhongshan building and its future. They became friends when they worked at Valentine Willie Fine Arts, and after the gallery’s closure in 2012, teamed up to form OUR Art Projects in 2013. Before the ground floor gallery in the Zhongshan building opened in late 2016, they had organised pop-up exhibitions in various spaces around Kuala Lumpur.

The Zhongshan project got its big break when it received a grant from urban regeneration organisation, ThinkCity, whose agenda is to bring the arts and its people back to KL. At the time of my visit, OUR Art Projects was exhibiting Mark Tan’s ‘Arrangements’, a monochromatic meditation on memory and identity. The exhibition is multidisciplinary and contemporary, hallmarks of the artistic ethos of OUR Art Projects and the Zhongshan building at large. When the women looked back on past exhibitions, they realised the artists they worked with practiced across mediums. “We were not aware we had wanted multidisciplinary artists,” Ng says. “But we realised they’re all outsiders … Those we have worked with are filmmakers, or they’ve studied business, or are conceptual artists. It’s all very similar to how we are in the arts, and how we have conceptualised this place.”

Mark Tan, ‘APIECE I-II’, 2014. Image courtesy OUR Art Projects

The Zhongshan, in a past life, housed a butchery, as well as the Zhongshan Association clan, of which Ho’s grandmother-in-law was part of. “The company was set up in 1962, and she slowly bought it up one by one, until she owned the whole place,” Ho says. The space later came to Ho by way of her mother-in-law who had no plans for the space.

Right now, the building is being marketed as an arts hub — a community centre that’s bringing together a host of seemingly mismatched artists, archives and collectives, giving them a space and drawing them back to the city centre. Over the past few years, various art spaces in Kuala Lumpur have either shuttered or moved on to cheaper, more inaccessible pastures, as skyrocketing rents and developers edged out artists. “I think the arts scene has moved out of KL. A lot of studios have moved out to Puchong, Rawang and places like that,” says Ho.

Currently, there are around 17 artists and collectives poised to occupy the building, among them individual artists — such as Yee I-Lann — the Malaysia Design Archive (MDA), lawyers Muhendran and Sri, Raman Roslan’s photo and video agency, a bespoke tailor (Atelier Fitton), the Rumah Attap humanities library, DJ collective Public School, and players from Malaysia’s alternative music scene.

The lit-up interior of OUR Art Projects gallery, featuring Nirmala Dutt’s posthumous exhibition, ‘The Great Leap Forward’, 2017. Image courtesy Karya Studio

It turned out that the current iteration of the Zhongshan building was Plan B; initially, the women wanted the building to serve as a kind of incubator for individual artists, which would have cost them time and resources that they didn’t have. “Doing it meant we’d have to quit our jobs to run this incubator,” says Ng. “So we scrapped that plan.”

In addition, the duo realised that they did not have the facilities and equipment, such as a printing machine, to make it work. “So I think when we look back at how we have silkscreen artists, how we have music people, archives, books—that’s what we wanted all along,” says Ho. “It doesn’t have to run with us. It’s easier for them to bring over what they have.”

This leads one to wonder if it is all sustainable. Multidisciplinary artist Chi Too says that there was a lot of skepticism regarding the Zhongshan building’s long-term future. In Malaysia, these kinds of initiatives have a habit of disappearing into the ether, so the hope is that by placing the building in the hands of many, the communities would benefit from bigger audiences and non-exclusive patrons. “We are all sharing audiences,” he says. “In a way we’re expanding our audiences, and that really helps with the sustainability of independent industries and businesses.”

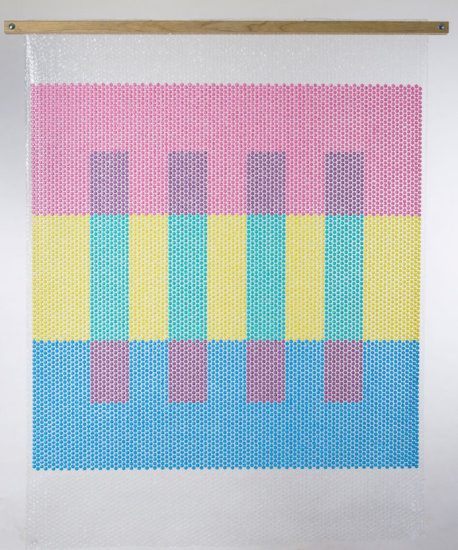

Chi Too, ‘Like Someone in Love’: (from left) LSIL #4, LSIL #12 and LSIL #6, 2014. Image courtesy Amir Shariff

Had the Zhongshan building become an arts incubator, it might have missed out on playing a vital role in establishing much needed infrastructure for the arts scene to truly take seed. Incubators, by nature, are solitary, but also dependent on the singularity of the individual; artists compete, they focus in on their work, and then they depart. The insularity of the scene would be a poison unto itself.

The vision of the Zhongshan building boils down to an ideal of community and a sharing philosophy that seems quite alien to an arts scene largely commanded by capitalist sentiment. Show Yung Xin, who runs the Rumah Attap humanities library, says, “It is not only a physical space for them to gather, but also a space for different communities to congregate, because before that, the arts scene was all within their own boundary, with the civil society and the activists are in another sector.” Communities that traditionally hovered on the fringes are now being brought together in a science experiment testing the hypothesis that the fringe does not need to kowtow to the mainstream in order to survive.

“The fact that the fringe exists simply means the fringe is sustainable,” says Chi Too. “Just because it does not earn as much money as the mainstream does not mean it can’t sustain itself.” Echoing this sentiment, Ho says, “I think if we can organically foster more collaborations, that would be. There’s people doing similar things that they can potentially collaborate on.” Already, they are pushing for the future residents of the building to begin speaking to each other, and to engage and find new ways to work together.

Chi Too, ‘Like Someone In Love #7’, 2014. Image courtesy OUR Art Projects

Establishing a culture of reflexive collaborative community lies at the heart of the vision that Ho and Ng have for the building. For them, without this connective force, it’s unclear whether or not the Zhongshan can truly survive. “Collaborations. That’s what this whole building is for,” says Ng. “So we thought, why don’t we join forces with all these indies, and then we’re a big indie, but still it can be whatever it wants to be. But it’s a progressive transformer, if I can put it that way.”

“We’re like Mama-san’s!” joked Ng. “Whenever people come to visit the gallery, we take them on tours of the whole building.” The women are actively working to bring outsiders into the insular art world, and also to encourage artists to enter into working relationships with one another. Hopefully then the Zhongshan’s nascent artistic community can evolve into a long-lasting culture. Already some collaborations are beginning to bear fruit: MDA and Ricecooker are planning showcases that blend their music and visual resources, while Tandang and Bogus Merchandise have longstanding relationships that feed into the Malaysian alternative music scenes.

Tandang Record Store in the Zhongshan Building. Image courtesy Choi

As Ho rattled off the list of tenants, it seemed like everyone was bringing their own friends and collaborators to turn the place into an arts kampung. Tandang Record Store and Bogus Merchandise have been introduced by Joe Kidd, who runs Ricecooker Archives. Raman Roslan plans to bring in indie publisher Rumah Amok, as well as the Kenyah sape player, Alena Murang, who has been making waves in the local music scene.

The concept of an artistic commune feeding itself is visibly referencing similar communities that already exist in the West. “It’s not a new concept but it takes a lot of work for it to work,” says Ng. “There are some parties that need to do the nurturing. Now that you’re an anchor, you actually have to anchor these things.” On their own, these indie groups might forever stay under the radar, but by pulling together these communities, the tenants will feed into each other and organically grow a foundation from which others can benefit from and engage with the arts.

“Personally my practice does not require a studio, but I do think — and as much a sociophobe that I am — as an artist it’s important to have community,” says Chi Too. “It’s important to be able to bounce things off other people, to rub off other people’s ideas and thoughts because I think the biggest problem with artists is how insular we are.”

Words by Samantha Cheh.

From: Art Republik. This article is the second installment of the four-part ‘More Life’ series covering visionary — and determined — individuals who are breathing life into the art scenes in Southeast Asian capitals.

For more information about OUR Arts Projects, go to: http://ourartprojects.com